Today’s hook

When you think about an anxiety disorder, what’s the first image that comes to mind—emotional weakness, lack of control, “it’s all in your head”?

The core message of the classic paper “The Neurobiology of Anxiety Disorders: Brain Imaging, Genetics, and Psychoneuroendocrinology” is the opposite: pathological anxiety is deeply biological, with well-described circuits, hormones, genes, and brain-imaging patterns. (PubMed)

Even though it was published in 2009, this work still serves as a kind of structural map for understanding why panic disorder, social anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and PTSD overlap in some ways but also have distinct signatures—and why a single treatment can sometimes help across multiple diagnoses. (PMC)

Today I want to translate that map into clinic language: where anxiety “lives” in the brain, which chemical messengers are involved, and how genetics and stress interact to raise (or not raise) a person’s risk.

The simplified deep dive

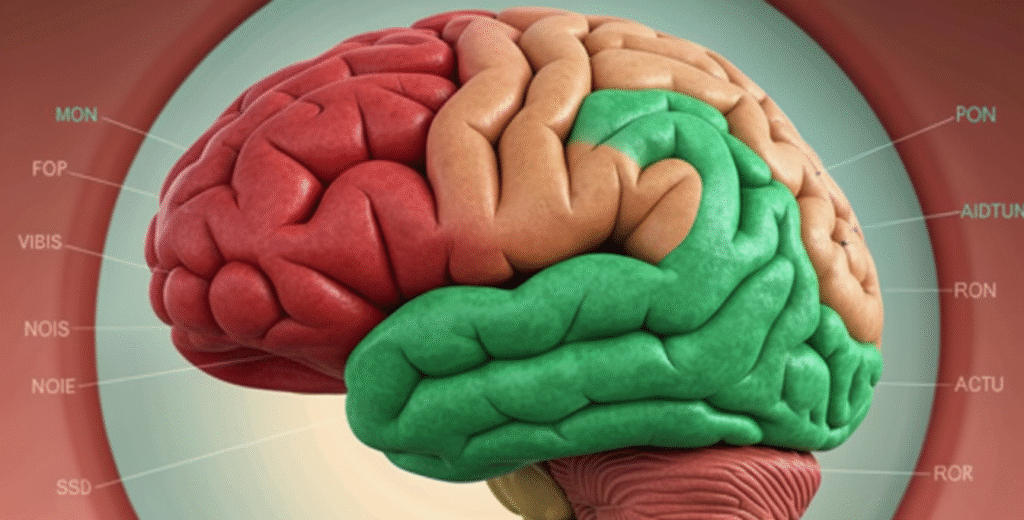

1) The core circuit: a “revved-up” amygdala, a cortex whose “brakes” don’t hold

The paper starts by reviewing the functional anatomy of anxiety. The key idea is that symptoms arise when there’s an imbalance between: (PMC)

Emotional centers (the limbic system)

- Amygdala: detects threat and triggers fear/defense/vigilance responses

- Hippocampus: provides context for memory and inhibits the stress axis (HPA)

- Cingulate cortex and insula: integrate bodily sensation, pain, emotion, and attention

Control centers (the prefrontal cortex)

- Dorsolateral and ventromedial PFC: planning, consequence evaluation, and the “cognitive brake” on emotional reactions

- Orbitofrontal cortex: rapid risk–reward assessment and impulse regulation (PMC)

In plain terms:

The amygdala is a hyperreactive smoke detector.

The prefrontal cortex is the rational firefighter who arrives late—or without enough pressure.

Brain imaging studies across panic disorder, social anxiety, PTSD, and GAD repeatedly show this pattern: increased activity in the amygdala and other limbic areas, alongside alterations (often reductions) in prefrontal regions that are supposed to modulate that response. (PMC)

2) Chemical messengers: GABA, glutamate, monoamines, and CRF

The paper walks through the major neurotransmitter systems involved: (PMC)

GABA (inhibitory) vs. glutamate (excitatory)

- Less GABA or more glutamate in limbic circuits makes the emotional network more excitable.

- That helps explain why benzodiazepines (which enhance GABA signaling) can reduce anxiety.

Monoamines: serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine (NE), dopamine (DA)

- Drugs that modulate 5-HT and NE (antidepressants, especially SSRIs) are effective across multiple anxiety and depressive disorders.

- That’s why genes involved in transporters, receptors, and enzymes in these pathways (like SERT, MAO, COMT) became major research targets. (PMC)

Notable neuropeptides

- CRF (corticotropin-releasing factor): a driver of the HPA axis; elevated in major depression, panic disorder, and PTSD, and linked to stress hyperreactivity

- Vasopressin, oxytocin, NPY, CCK, galanin: modulate stress response, social behavior, and vulnerability to anxiety/depression—sometimes anxiogenic, sometimes anxiolytic depending on the pathway (PMC)

Think of these systems like a control panel: when multiple switches are dysregulated at once (less inhibitory braking, more excitation, higher CRF tone, monoamines out of balance), the brain becomes more likely to interpret neutral cues as threatening—and to keep the alarm system turned on.

3) The HPA axis: when the stress system gets stuck in “alert mode”

Another pillar of the paper is the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, the hormonal stress response system: (PMC)

- A perceived threat activates CRF neurons in the hypothalamus.

- CRF stimulates the pituitary to release ACTH.

- ACTH stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol.

- The amygdala tends to increase HPA activity.

- The hippocampus provides “braking” via negative feedback once the stressor passes. (PMC)

Chronic changes in this axis can look different depending on the condition:

- Major depression: often HPA hyperactivity (Dex/CRF testing often abnormal)

- PTSD: in many studies, a near-opposite pattern with relative HPA hypoactivity—despite heavy stress exposure and prominent anxiety symptoms (PMC)

So even when symptoms can look similar clinically, the underlying stress-axis “settings” may differ—helping explain differences in course and treatment response between PTSD, depression, and other anxiety disorders.

4) Genetics, environment, and anxiety: not “weakness,” but built vulnerability

The genetics section reinforces a view that’s close to consensus today: there’s no single “anxiety gene.” Instead, many variants increase vulnerability, interacting with environment across development. (PMC)

Key points the paper emphasizes:

- The same gene systems that modulate the HPA axis and monoamines show up in risk studies for both depression and multiple anxiety disorders.

- Child studies suggest a dynamic pattern:

- at certain ages, some genes matter more

- at other life stages, the “relevant” genetic set shifts—consistent with the idea of sensitive windows for anxiety development (PMC)

And perhaps most interesting:

- Epigenetic mechanisms (like promoter methylation in stress-related genes) allow life experiences to “write” risk or resilience into functional gene expression—without changing the DNA sequence itself. (PMC)

Bottom line: clinical anxiety is brain + genes + life history, far more than “lack of willpower.”

Implications and invitation

What do I take from this still-useful paper into practice—and into how we talk about anxiety?

It moves anxiety out of morality and into biology.

When we show patients (and ourselves) that circuits, hormones, and genes are involved, we create space for treatment without guilt: medication when appropriate, psychotherapy, and lifestyle interventions.

It explains why multiple treatments can work at once.

- SSRIs target monoamines

- benzodiazepines target GABA

- CBT strengthens the prefrontal “brake” over the amygdala

- meditation and exercise modulate the HPA axis and limbic circuitry

Different roads, same ecosystem.

It opens the door to biomarkers and more precise treatment.

As imaging, genetics, and endocrinology improve, the trend is to move beyond a generic “anxiety disorder” label toward subtypes defined by biological signatures, not just symptoms.

My personal takeaway: this paper is a reminder that anxiety is neither “only psychological” nor “only chemical,” but a continuous dialogue between brain, body, history, and context. Understanding the biology better matters not just for developing new drugs, but for reducing stigma and sharpening what we do in clinic every day.

That was today’s dose of science in the Medical Innovation column.

Now I want to hear from you: in your practice, does talking about brain biology help anxious patients engage more with treatment—or do you still run into a lot of resistance and stigma? Share your view in the comments, and come back tomorrow—we’ll keep tracking what neuroscience is revealing about mind and mental health.